Contradictions of Land Market Transaction – A Critical Case from Shenzhen, China is my Master’s thesis at Harvard University Graduate School of Design, which I defended in May 2017 and was awarded distinction. The research was funded by Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. It extended my LSE dissertation, which investigated the institutional arrangements in China’s urban redevelopment schemes, but here I further explored the issue’s spatial implications and ultimately questioned the existing thoughts and methods of urban planning and design. I felt extremely fortunate to have had Professor Diane Davis as my thesis advisor. Coming back to the GSD determined to pursue social sciences instead of design, I realized that I was quite an outsider. It was her absolute understanding and crucial intellectual guidance that enabled me to assert all of my skepticism, criticism, and hopefulness into the thesis.

In rapidly transforming urban societies, architecture and physical construction are often inseparable from the political and social aspects of development. The Chinese government has long been powerful in steering urban redevelopment across the country. However, in the southern Special Economic Zone of Shenzhen, urban development follows a different path. In Shenzhen, the market force has largely replaced the public sector in the rebuilding of what has been known as urban villages. My case study site, Dachong, used to be such an urban village characterized by dense building construction and informal land tenure. The high transaction cost of dealing with informal land should have driven the developers away, but in reality, Dachong was successfully acquired and transformed by a real estate firm. So I wondered: How did the developer overcome the obstacles during land acquisition without the use of political coercion? When a developer is involved in the redevelopment of urban villages, what happens socially?

(Dachong Village before redevelopment. Picture credit: UPDIS)

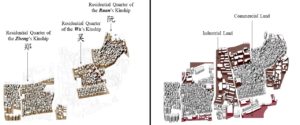

To understand the story of Dachong’s transformation, I looked back into the village’s pre-development past. Despite its high density and the seemingly chaotic urban fabric, Dachong’s physical layout followed a clear structure. The three residential quarters were distinctly defined and corresponded to the three existing kinships in Dachong. Each kinship is a big family, within which the members were close to each other, observed the same customs, and shared the same way of life. The land in between the residential quarters was for industry and commerce, which brought revenue shared by the entire village; in 1992, the village established Dachong Corporation to replace the former village government as the legal entity owning these collective assets.

Dachong Corporation managed land and properties of such great magnitude thanks to the unique social and governance structures of the traditional community. Stemming from village values, Dachong’s strong leadership and representative democracy facilitated the top-down style of management. The Corporation further improved the organizational efficiency of the village by forming kingship-based subsidiary companies; each of the subsidiaries became a small group, which was quick and effective in resource mobilization and conflict resolution.

Such a high level of social solidarity turned out to be helpful to the real estate industry that sought to transform the village into new development. During land acquisition, instead of negotiating with every property owner, the developer could concentrate most of its resources on the patriarchs and local leaders; the governance structure and the kinship culture then helped to secure the entire village’s cooperation, greatly reducing the developer’s cost of negotiation. (Regarding the legal and political nuances in this negotiation process, please see Section IV.5 of my LSE dissertation.)

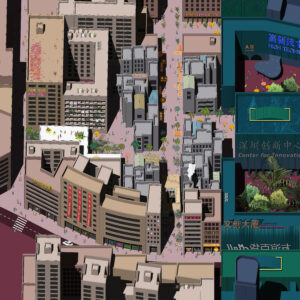

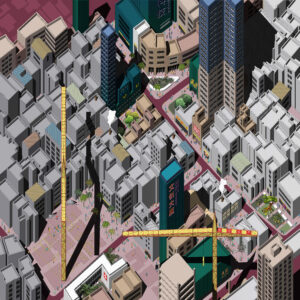

After the deal was made, it is according to Shenzhen’s planning principle that the government should consolidate the fragmented land parcels into one unified lot and then transfer the development right to one entity. In the case of Dachong, the real estate firm obtained the land right, rebuilt the entire area, and constructed 30 million square foot of new properties such as housing, hotels, offices, stores, and schools. Part of the new housing and commercial properties were built for the villagers and the Corporation. In fact, 35% of the new properties were given back to the village as compensation.

In a way, the redevelopment of Dachong was a huge success. At the time of my study, it was the largest urban redevelopment ever accomplished in Shenzhen. However, there were also problems in its afterlife. Although the village received commercial properties as compensation, the stores have been largely empty and the momentum in their operation and development lagged behind the developer-operated properties across the street at the time of this research. This was because commercial development needed the agreement and collaboration among villagers, but after the redevelopment, Dachong no longer had the same level of solidarity.

Three processes induced the sudden loss of trust in the redeveloped village. First, the developer built a gated community to house all three kingships that used to occupy separate territories. The cultural identities of the different groups were erased in the homogenous high-rise residential towers, and the social distance between residents was enlarged, making collaborations and collective actions, which were so vital in the management and operation of village assets, became difficult after redevelopment. Second, despite the general consensus in Dachong during redevelopment, a number of villagers considered the negotiation process to be nontransparent and the distribution of profits unfair, which could exacerbate the economic inequality in Dachong, breaking the villagers’ trust in their leader. Last, Dachong Corporation’s initial plan to retain ownership of part of the site and act as a co-developer was revoked in the final deal, partially because the existing regulation allowed only one entity to redevelop the land. This worsened the relationship between the village and the developer. (Again, for more nuanced details and analysis, please refer to Sections IV.5 and V.3 of the LSE dissertation.) In the end, villagers no longer trusted each other, they did not trust their leader, and the village lost trust in the developer.

Therefore, during the overall course of redevelopment, social institutions such as trust, solidarity, and indigenous governance structures initially enabled smooth and efficient negotiations. However, due to insufficient transparency and lacking participation in the process, the communal bonding was weakened, and the spatial result out of such imbalanced negotiations eventually broke the social ties. Developers and planners should be concerned about this dynamic, because urban redevelopment does not stop when the new buildings are completed. The ongoing commercial and community development will always require people’s close collaborations. Without solidary and trust, new problems in the social, economic, and physical spaces will further paralyze the site.

From an institutional analysis perspective, the existing redevelopment process backfired because the requirement to consolidate the land and give it to one entity negated people’s ability to arrange social and economic relations in complex yet useful ways. Developers are often more politically and financially powerful than the village collective. Without a mechanism for fair coexistence, the power imbalance between stakeholders tends to worsen. Through spatial configurations, different groups could have manifested their coexistence. Before redevelopment, the village lived with multiple layers of consensus building, and such a complex social structure is embedded in Dachong’s hybrid spatial configuration. On the one hand, people localized their kinship cultures in distinct residential quarters; on the other, the collective space between the quarters allowed the multiple groups to share a larger vision of living and development. During the redevelopment, however, because landownership had to be consolidated and given to one entity for redevelopment, the party with the most political and financial prowess would win the negotiation and decide on the overall configuration of space; the other party, instead of finding creative ways of co-development, was only allowed to receive the constructed properties according to the negotiated deal. Although the village indeed took an advisory role in the design phase, the final spatial layout mainly reflected and perpetuated the negotiation’s imbalanced power dynamics. In this mode of redevelopment, space is the merely the end, not the means, of urban transformations.

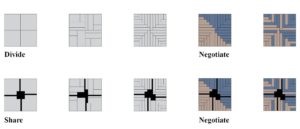

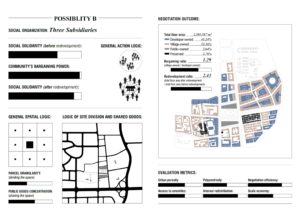

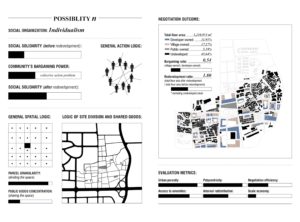

In the search for an alternative redevelopment model, my thesis challenged the consolidation-based paradigm of land transactions and argued that space is a method and an agency that can enable parties of different interests to create new relationships and experiment with institutional innovations. The alternative model should leverage the place’s preexisting social solidarity for smooth transaction but avoid the exploitation of imbalanced negotiation process that generates harmful social and spatial outcomes. So, I proposed to tweak the planning rule a little bit by allowing the subdivision of land in Shenzhen’s urban redevelopment. Instead of having one entity take the consolidated land in its entirety and negotiate with the other regarding the compensation package, my proposed rule allows the developer and the village to negotiate their ways of subdividing the land, each obtaining their own right to develop distinct parcels. Then, in between the blocks owned by different entities, shared elements will be inserted to provide public spaces such as parks and plazas as well as public amenities such as schools and hospitals. The parties will then negotiate again to address how they will share these public elements and how parcels of different ownerships should relate to each other spatially and programmatically.

This proposed framework aims to explore the institutional role of physical planning. Subdividing and sharing the land can open up more windows of negotiations for the parties to find out their potential conflicts and address them by arranging the space, increasing the process’ transparency, inclusiveness, and balance. Essentially, what I was doing is putting spatial design not only in the final architectural stage that passively builds out the negotiation outcome, but in the initial stage of institutional design that governs and anticipates the negotiation process. My goal was to make the policy framework more spatial, as well as to make design more institutional.

How exactly the village and the developer will subdivide the land and who eventually gets what will depend on how the stakeholders negotiate – the government should regulate to ensure procedural transparency but try not to intervene or exert unfair influence. What planners and regulators can focus their energy on is the design of public elements that anticipate and facilitate the stakeholders’ negotiations. In order to make the subdivision and sharing of land practical and useful, planners should structure the road network strategically to produce reasonably sized land parcels. Public spaces and amenities should also be designed and positioned accordingly for their desired area of impact. These key spatial and programmatic features cannot be arbitrarily designated. In the land sharing model, planners should design the roads and public amenities with the place’s social structure in mind, because understanding the level of social ties can help the planners estimate how the stakeholders would act to use and operate collective resources.

However, planners cannot just always assume strong and perpetual social solidarity. In fact, the level of communal ties in urban villages of Shenzhen has been changing as the city grows. Although it was Dachong’s redevelopment scheme that precipitated the village’s drastic change towards individualism, the community’s long-term interaction with outside citizens and the increased educational attainment of Dachong’s newer generation had already been slowly moving the village away from its traditional social and governance structures. If the newly proposed planning rule is to work more generally in the city, it must be robust and flexible under different social scenarios. Were Dachong to be redeveloped at a different time, the process and the outcome of negotiations might be different. For planners, the physical infrastructure of roads and public amenities should reflect and work well with the actors’ different social structures and behavioral logic.

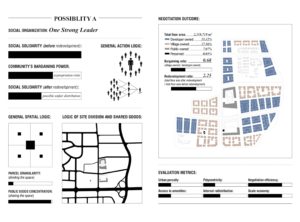

To test the new model, I present below the projections of three redevelopment possibilities, assuming three levels of social solidarity – extremely high, extremely low, and a place in the middle. I used architecture as a research tool to model the three possible outcomes of redevelopment and compare their potential differences. The estimates were based on the understanding that different social structures bring about different negotiation dynamics.

Each of these scenarios demonstrates the tradeoff between negotiation efficiency, the village’s bargaining power, and the overall effects on post-redevelopment social solidarity, scale economy, and urban quality. Estimating, visualizing, and understanding these potential differences can help the stakeholders to think more broadly and strategically about their plans and decide on the most optimal entry point for redevelopment. Those who aim to maximize short-term gains should aim to redevelop the site when the level of social solidarity is the highest. Those who hope to preserve and strengthen the place’s social ties for long-term development should set the entry point at the time when the community demonstrates some level of federalism. Smaller parties with individualistic demand and niche expertise should wait until the village is no more socially different from the rest of the city.

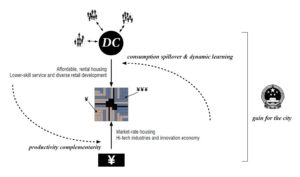

For the city government, the land sharing model is a step forward greater local economic efficiency. When the village develops its own land parcels, it can choose to specialize in sectors and activities that the village has a comparative advantage of. Instead of receiving office towers and hotel buildings from the developer as part of the compensation package, the village can build and operate service economies and manufacture in addition to retail and rental housing. The developer-owned real estate can then specialize in attracting hi-tech and innovation economy. The high-skill sector will benefit the less skilled via consumption spillover and dynamic learning; the latter’s presence is helpful to the former due to productivity complementarity. These economic effects will benefit the city as a whole. As for policy implications of the new model, the city government should build a transparent market for land transaction by and refrain from intervening in the stakeholders’ negotiation process. Without a level playing field, it will be impossible for the real estate firm and the villages to subdivide and share the land that produces optimal social and spatial outcomes. The banking sector should also begin to think about options for the village collectives to obtain construction loans when they can act as co-developers of urban land.

From the initial fieldwork to the final policy proposal, I had to reflect many times on the relationship between research and design. This thesis is split into three parts: an empirical research that started from my LSE dissertation, a policy proposal, and a comparative study based on design visualization. My level of self-confidence decreased drastically as I moved from Part 1 to Part 3, because the number of assumptions I had to make increased as I moved from research to design. In the end, I found myself making architecture in a very strange way in the final part of the thesis. When I drew the buildings and designed the urban spaces in the three scenarios, I was not trying to designate the dimensions and proportions of physical structures based on my aesthetic preferences. What I was doing is to estimate what the spatial outcome might look like based on the theory that social structures affect the built environment via their influence on people’s logic of collective action – this theory is essentially what I tried to explore and test during the empirical research. I did the best estimate that I could do to model what the place might be like given different levels of social solidarity. Architecture for me thus became purely illustrative; it was like a camera with which I could document the situation as is and show it to the interested audience, nothing more. This is how I chose to limit the agency of architecture and design. However, my projections and estimations can also be imprecise because social structures are not the only determinant of people’s action. This is where I realized the limitation of social sciences.

I wouldn’t have the strength and courage to admit those limits and present this project without the guidance from my advisor Diane and help from my friends Juncheng Yang and Teng Xing. Besides those who helped with my LSE dissertation, I also hope to extend my gratitude to Professor Sai Balakrishnan, Professor Peter Rowe, and Professor Jian Liu for their very constructive criticism and advice during the design phase. I couldn’t have been happier to conclude my journey at Harvard GSD with this project.

Recommended Citation:

Luo, Yuxiang. 2017. Contradictions of Land Market Transaction – A Critical Case from Shenzhen, China. Harvard University, MArch Thesis.