(Picture credit: John Paraskevas, Newsday)

This was my very first studio experience at Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Offered by the Department of Urban Planning and Design in 2014, the studio invited students of different disciplines to study the demographic and environmental changes that happened in Long Island – the once famous suburbia currently facing complex challenges regarding racial segregation, aging, nimbyism, and poverty. It was an extremely fun and eye-opening experience that Professor Daniel D’Oca led with ambition and care, and I learned so much by collaborating with my classmate Tamotsu Ito for this unusual project.

(Picture credit: John Paraskevas, Newsday)

The project started from our meeting with Margarita Espada, an artist and community leader based in Central Islip, New York and founder of Teatro Yerbabruja. Central Islip is a Long Island suburban neighborhood troubled by great tension among its immigrant residents, unattended children, segregation of schools, and general political inactivity. In reaction to such a condition, Margarita aimed to use art as a catalyst of social change, and she pitched to us the idea to refurbish a small building on the main street and transform it into an art center that could function as a community gathering place.

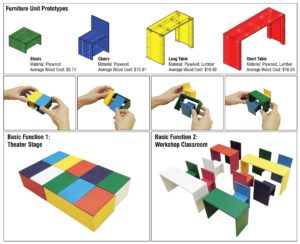

Instead of just giving her the art center, we took a more systematic approach and conceptualized the project as a system of three distinct yet interconnected components. We hoped to use small, tangible elements to leverage larger social impact. The smallest scale of our proposal is the theater design; it is a quick action to jumpstart the project. The client needed the art center space to accommodate both performing art events and classroom functions; while talking to many local stakeholders, we also discovered many other possible scenarios for the center’s programming. Through back and forth communications, we developed a flexible furniture set that could transform from a stage to tables and chairs. Such a design enables performing art and other programs to coexist. Modular design makes the simple furniture sets capable of producing various spatial arrangements, activating the users’ imagination and customization.

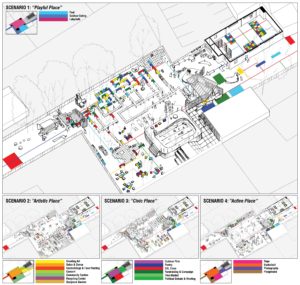

For the next scale, we addressed the backyard space. As a future “public living room” for the neighborhood, this outdoor space needs to be vibrant and appealing. At the site’s four corners, we placed several anchor points to house programs that reflected local needs, such as community garden, playground, and recycling. The larger space in the center can be open and flexible, accommodating events curated by the art center.

Finally, the largest scale is a strategy to build social capital through the art center. Margarita envisioned the art center as a starting point to revitalize the local economy and integrate different sectors of the neighborhood. Therefore, we pushed the facility beyond its physical scope; we proposed that the art center should be conceptualized as an inventory system, through which local residents and organizations can exchange their diverse needs and resources. For example, if a person bought a house with unfurnished rooms, the art center could provide artists to help her decorate the new home. In this simple scenario, the person provides a space resource, and the art center provides talent; this process can slowly cultivating a new type of neighborhood economy in Central Islip.

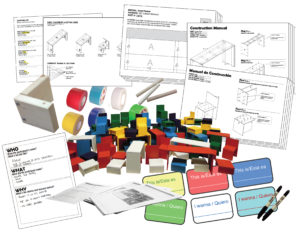

Besides giving Margarita the ideas, we also helped her deliver the first step of implementation. Believing that the process of building the art center would be a good opportunity to leverage social integration, we organized a series of events to engage the community. First, we collaborated with the NGO Sustainable Long Island to design and distribute a survey asking for the residents’ design input and pushing forward the art center’s initial round of marketing. Then, we planned a DIY event for the residents to build the furniture pieces themselves. In preparation for the event, we designed tools and easy-to-read instruction manuals (in both English and Spanish) that helped the untrained residents to fully participate in the construction and customization processes. On the Thanksgiving weekend of 2014, 32 residents volunteered in our DIY event. With a budget of $1,500, we were able to make 24 chairs, 4 long tables, 6 short tables, and 24 stools in just one day, all painted in bright colors. Through making, different members of Central Islip came together, talked to each other, had fun, and took pride in what they achieved together.

In addition to constructing the furniture sets, we made miniature models of the design and invited residents to play with these toys. Via playing, people discovered more possibilities to use these furniture pieces inside and outside the art center building. By telling each other what they wanted and why, residents of Central Islip listened to other people’s stories and began to envision a future for their neighborhood together.

The future imagined by the community has a strong potential to be implemented in reality, because the residents have already made the building blocks together with their own hands. The art center is a testing ground for public imagination, enabling the community to form social ties and build out their future together.

After the successful DIY event, we reflected on the process and drew eight lessons about public participation. The lessons can be accessed here. Despite the acclaim received in the final project presentation at Harvard GSD, I do not believe that design can single-handedly solve social issues. Design can offer a fresh mechanism for stakeholders to come together and envision their future, but financing and management are indispensable in order for community programs such as the art center to stay true to their visions and succeed in the long run.